The Great Famine of 2006: A Growing Chorus of Outrage

When it comes to North Korea, food aid is not our weapon. It’s already North Korea’s weapon. Our goal should be to feed as many innocent people as we possibly can, with or without the North Korean government’s cooperation. The distribution of food is the most important human rights issue of all.

I’ve been tracking the reports of a return of famine conditions closely this year, but it wasn’t until several days about that I became convinced that North Korea was serious about cutting off food aid, something I’m convinced will kill millions. Fortunately, the news media appear to have noticed the story, and this may save lives. The BBC takes the highly unusual step of criticizing the productive disincentive of socialism, and then says this:

The problem with this system is that market reforms, instituted in 2002, have sent prices soaring at a higher rate than wages. “Who can afford this stuff in the markets?” asked Mr French.

The answer: only the elite. Government officials, senior managers of state enterprises, security forces, and the leadership of the army are all unlikely to go hungry.

But a typical urban family can now only afford to buy 4kg of maize – the cheapest commodity – a month.

The quote has a familiar ring, and an intrepid googler with more time than I might be able to confirm that the BBC has printed this quote before. That doesn’t deprive it of veracity. The BBC may also be a step behind in another way–for not having read Prof. Andrei Lankov’s report that the regime is trying to reconstitute its Public Distribution System, perhaps to regain control that they never really intended to relinquish in the first place.

The L.A. Times, which long ago outran the WaPo and NYT in quality of coverage on humanitarian issues, also covers the story (registration is free):

U.N. humanitarian affairs chief Jan Egeland said Friday that North Korea was not ready to feed its people on its own, and that he was trying to persuade Pyongyang to continue food aid to the country’s children.

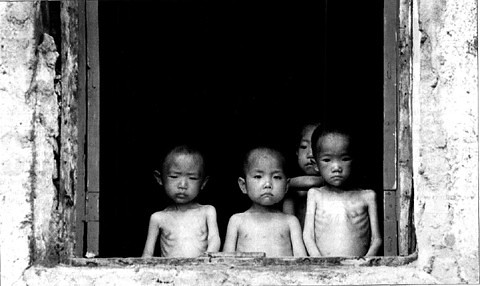

. . . .“My heart goes out, really, to the children of North Korea, and I appeal to the government to help us feed them,” Egeland said.

. . . .The isolated nation, which has a policy of juche, or self-reliance, faced severe famines over the last decade that killed an estimated 2 million people. Though North Korea is better able to feed its population and expects a good winter harvest, about 7% of its 22.5 million people are still starving and 37% remain chronically malnourished, Egeland said.

“Our assessment is that they will not be able to have enough food,” he said. “We are very concerned because we think this is too soon and too abrupt. . . . .

Because North Korea will still accept development assistance, U.N. officials are negotiating ways to continue feeding the hungry in a different guise. Meals for schoolchildren could be reclassified as an educational program, Egeland said, adding that the World Food Program already pays some workers with food.Development aid, Egeland noted, typically is used to build infrastructure, bolster agriculture and promote self-sufficiency.

But some international donors worry that giving development aid makes them appear to endorse Pyongyang’s harsh communist regime.

“Many of them are not interested in that,” Egeland said. “They are interested in meeting humanitarian needs only. This could lead to a big decrease in programs.”

Among the Korean papers, the Korea Times has probably covered the story best. This Korea Times article details allegations by Rep. Chung Moon-Hun about the inequality of food distribution, and criticizes Seoul’s unilateralist policy of giving aid that is inadequately monitored (more on that here). The report comes complete with a province-by-province breakdown map. This is must-read stuff, and would merit an entire post by itself had I more time this week. More recently, it discusses the “baffled” reaction of foreign NGOs about Pyongyang’s expulsion order:

Radio Free Asia said that senior officials at NGOs, such as Ireland’s Concern, France’s Triangle Generation and Germany’s German Agro Action, are frustrated over North Korea’s decision to end their on-going aid activities.

Ann Omahony, head of Concern’s Asian affairs, said North Korean authorities have asked the NGO to hand over its work to them or to leave the country by Dec. 31. But it is impossible to do so because it defeats the purpose of NGO’s existence, the station quoted her as saying.

. . . .

According to the station, Patrick Valbluggan, chief of North Korean aid at Triangle Generation, is also at wit’s end over the North’s sudden request for a shift to development assistance.

Only a few weeks ago, Triangle’s staff were asked to leave the North by the end of this year without any reason given, he said.

The Joongang Ilbo has more. The Chosun Ilbo reports that the U.S. government is mulling over the WFP’s proposal to give North Korea its “development aid,” and is “would discuss the matter with the international community.”

The Daily NK has an interview with Marcus Noland’s partner in research, Professor Stephen Haggard of UC Berkeley. Again, this would be a blog entry in itself, but for the fact that I have two weeks’ worth of great material I haven’t had time to write, edit, and publish with the appropriate care. Haggard reports that even with current WFP efforts to monitor distribution, as much as 50% of the food aid is diverted. Clearly, more monitoring is necessary, not less. Another must-read.

Perhaps feeling the pressure to insert humanitarian issues–ie., the monitoring of food aid–into the nuke talks, North Korea stops to tell a transparent lie:

A source who recently traveled to the North on Tuesday quoted officials there as saying Pyongyang would normalize food rations on Oct. 10, which marks the 60th anniversary of the Workers Party of Korea. The source said he was told that cereal rations, which averaged 300 g a day per person and were cut to 250 g a day earlier this year, would be increased to 500-700 g from that day.

. . . .The World Food Program says North Korean authorities slashed per-capita cereal rations from 300 g to 250 g in January. That was the lowest amount since January 2001. The source said a normal adult should consume about 700 g a day.

The daily minimum for survival is 500 grams, and North Korea’s claims of a sudden capacity to provide it don’t jibe with recent reports in the least. Start with this one from earlier this year, which discusses the reduction to PDS rations to just 250 grams per person per day. This report quotes a South Korean agricultural expert, who expected a terrible harvest this year. Then read this appeal, and this one from August, from WFP country director Richard Ragan. The appeals suggest a slightly improved harvest but note that 6.5 million North Koreans–a third of the surviving population–still depend on WFP food aid.

Where did North Korea so suddenly and improbably get all this additional food? If the raised ration is as imaginary as it seems, what will the people of North Korea do? A final graf from the BBC report:

“I’m not in the business of predicting numbers that are going to die,” [WFP official Gerald Bourke] said. “North Koreans are very tough people. They are very accustomed to deprivation. But that doesn’t take away the urgent need for food aid.”

Note: A very, very big disappointment for me this week was that pressing work duties forced me to miss hearing the remarks of Andrew Natsios and Marcus Noland on food aid and famine in North Korea at the Woodrow Wilson Center yesterday. I’m trying to get copies of their remarks, and would appreciate any help on this (as if I’ll find time to write about it).