The Mad Kingdom, Part II: A Perfect Union of Imprisoned Minds

I am ready to pronounce a partial reversal of my view on North Korea’s Arirang Festival. For the little trifle that the North Korean regime hoped to earn from curious westerners or sympathetic South Koreans, they certainly did not expect to turn a profit. The real motives were domestic consumption and foreign propaganda–to show the world that North Korea is unified, stable, happy, and dangerous to any foe. If that was the motive, the resulting coverage fell dramatically short of expectations, for the coverage portrays North Korea as unhinged, scary, and unraveling even within its core areas in Pyongyang, and near the Kaesong Industrial Park.

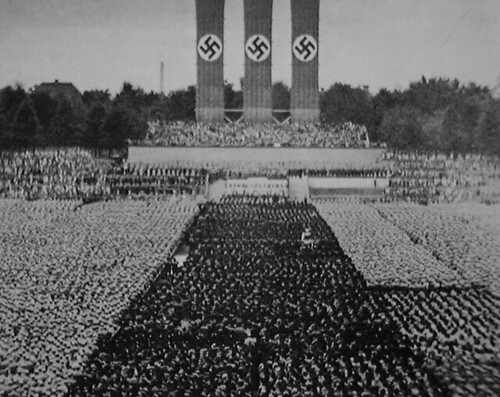

Scene from The Triumph of the Will (1934), directed by Leni Riefenstahl.

The Depressing Monotony of History: Arirang (photo by Thomas St. John)

Veteran journalist Don Kirk, who covered the festival for the Christian Science Monitor last week, also wrote an op-ed in the the Wall Street Journal Asia (subscription only):

It’s difficult to know whether to laugh or weep over images of what may rank as the world’s most bizarre theatrical spectacle. Here in the giant May Day stadium every night in recent weeks, some 50,000 young people have been flaunting flash cards in the grandstand while 15,000 prance and dance on the turf. They have been enacting visions of North Korea’s past, present and future sadly at variance not only with the images of darkened streets and empty highways that any visitor can see–but far more importantly, with the disease and hunger that have killed more than two million people over the past decade and the imprisonment and torture inflicted on many thousands more.

. . . .

Given the massive personality cult that lies at the heart of the North Korean regime, it comes as no surprise to see the festival venerate Kim Il Sung as a God-like figure. Tour guides, asked if they believe in God, insist the late leader is their God. Far more alarming: was the festival’s emphasis on the military, which has for years ranked far ahead of the Workers’ Party as the main pillar underpinning Kim’s dictatorship. Songs hail the glory of an “army-first policy” while soldiers, bayonets drawn, parade to shouts of “Military and the People.Â

What is more interesting to me today is the daily requirement–on pain of imprisonment, torture, or death–to deal with real people and situations as if they were scenes in an imaginary world. Natan Sharansky (and before him, George Orwell) have termed this “doublethink.” Not having lived in such a world, I can’t imagine what it must be like. One day, we may know more about the psychological effects of a life lived in one world and acted and spoken as if in another.

Most startling of all: the picture the festival seeks to portray of happy, full lives, joyous people, burgeoning agriculture and industry–all glorified in grating song and dance on the playing field, flash cards changing scenes so fast that it’s impossible to keep track of all the wonderful things supposedly happening in North Korea. Heartened that “our warriors are everywhere,” smiling kids appear in giant caricature thanking “Comrade Kim” for their “happy childhood” as they gambol on beaches. Quickly the flashcards switch to tractors in verdant fields, then to water gushing over dams, generating hydroelectric power, as flowers bloom, dancers leap in funky guise as bunny rabbits, chickens and pumpkins, and slogans in Korean flash across the stand, “Two Harvests a Year” and “Let’s Produce More Eggs and Chickens.Â

Kirk then notes that “you don’t have to stray far from the stadium to see hints of the real North Korea–even on such a closely chaperoned tour,” pointing to the unfinished hulk of the Ryugyong Hotel, the dark streets, and the crumbling highway leading from Pyongyang to the Kaseong Industrial Park. Kirk, accompanied by author Bradley Martin, noted the visible deterioration of the road since a previous visit a decade before. Even this is a very imcomplete picture. Few western reporters, if any, can expect a chance to observe conditions in North Korea’s blighted and famished northeast, where what we know suggests that things are much worse. But the poverty of the North Korean people is still visible:

Further afield, lines of hills stripped of trees by North Koreans desperate for anything to keep themselves warm offers a hint of the daily battle for survival in Kim’s giant gulag. But it’s impossible to gauge the full extent of the suffering that his regime continues to inflict on its long suffering people in a land where vast areas remain off limits to foreign visitors.

You’ll find no answers in Pyongyang, whose two million residents have been specifically selected for their loyalty to the Kim Dynasty. . . .

Kirk closes the piece by describing twenty to thirty truckloads of televisions–God knows how much milled corn could have been bought instead–being delivered to loyal party members for helping to bring the great illusion off. Then again, what are a few TV’s next to last year’s estimated $10 million in arms bought from Russia and China alone.

Kirk was not the only correspondent on whom the display failed to achieve the desired coverage. Even a stunning female guide failed to erode the cynicism of the BBC correspondent:

A few minutes later, Mrs Song and I are having our first row. She wants me to lay a wreath in front of a giant statue of the late leader, Kim Il-sung. “He is a god to us,” she says, a cult-like fervour in her unblinking eyes.

I decline. She threatens to have me deported. We’re really hitting it off.

As promised, the mass games are truly, unnervingly spectacular. Ten thousand students are crowded into the stands, holding up cards to form a giant, human TV screen. In perfect unison they keep switching the cards to form new patriotic slogans or images from Korean history. On the stadium floor many thousands more dance and march and twirl. Endlessly. Nobody makes a mistake.

Then comes this vignette from one of Pyongyang’s high-priced hard currency stores, which will undoubtedly make work for some of the researchers at the CIA:

I spot a fair-haired young man at the counter, buying a load of crackers and biscuits. He is clearly Caucasian – maybe 20 years old – but he is wearing a local suit with the standard Kim Il-sung badge on the front.

I walk over. He says he is American then quickly corrects himself: “I’m Korean. I was born here. My father is from America.” “Really,” I say. Perhaps his dad was one of a handful of soldiers who defected during the Korean war. “How did your father end up here?” Long pause. “I’m sorry,” he says, looking sheepish. “I cannot say any more.” He shuffles away across the store.

It doesn’t sound like the response one would expect from a visiting KFA member. Later, the correspondent sees citizens selling what appear to be personal possessions by the side of the street. The crew starts filming, but the guides demand they stop filming and hand over the tape. This sets off another argument between the correspondent and his minder:

We just want to talk to ordinary people,” I tell Mrs Song. “But you can talk to me,” she says. “I am ordinary.”

Finally, late one night, we manage to slip away from our hotel unaccompanied. The streets of Pyongyang are dark and silent but full of people walking. Soldiers mill around by the train station. We talk to a couple of women selling blueberry juice. Is life getting easier? “Well, we get by,” says one. “Thanks,” she quickly adds, “to our Dear Leader.” I am the first foreigner she has ever spoken to.

Of course, not all of the views were so circumspect. There are species of humans who are awestruck by the mass dehumanization of others–and this is the very least you can call turning a human being into a pixel on big-screen TV for despots and the foreign admirers invited to go slumming in their overwrought rec rooms. We learn from one of them that apartments darkened by the loss of power can be eerily beautiful (provided, of course, you don’t have to live in one).

Ever considerate, Kim toned down the anti-Americanism for them this year, perhaps in a tip of the hat to Hitler’s nuanced magnanimity in letting Jesse Owens run, and taking down the “Judenrat” signs until the tourists were safely home, telling their friends about the soul-smothering, splendid choreography of Nazi calasthenics. But in the West, Arirang was a dismal propaganda failure, and that is a good thing. What is decidedly less positive is this massive misallocation of resources by a starving nation, the lives it undoubtedly cost.

2 Responses